More Treaty Gridlock: Another Impact of GOP Senate Takeover

More on:

The Republican takeover of the Senate reduces the chance that the United States will ratify any important multilateral treaties over the next two years. Facing a GOP-controlled legislature, President Obama will focus his executive authority on salvaging what remains of his domestic agenda, rather than playing hardball in the field of foreign policy.With the exception of trade agreements—endorsed by incoming majority leader Mitch McConnell—don’t look for any movement on treaties.

While the Senate has long been known as the graveyard of treaties, that metaphor is particularly apt today. Even before November 4, securing the U.S. Senate’s advice and consent to multilateral treaties was rare. But since President Obama took office, the United States has ratified a grand total of six multilateral treaties. Eight of the eleven multilateral treaties the president has signed during his term remain unratified, as do twelve of the thirteen multilateral treaties signed by previous presidents which the White House included in its “treaty priority list” communicated to the Senate in 2009. The GOP triumph last Tuesday will only reinforce this gridlock.

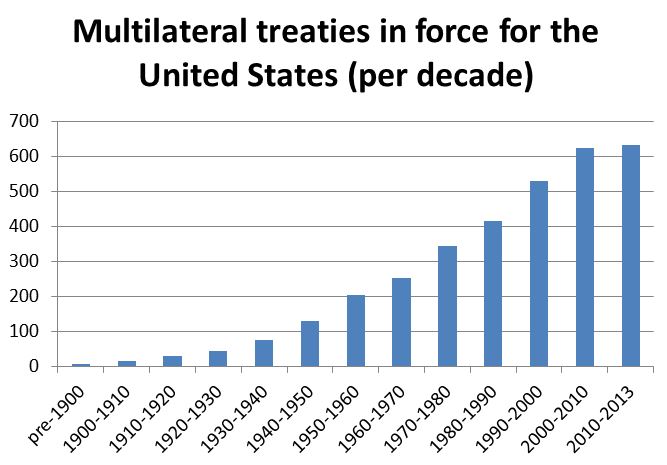

It was not always thus. Despite admonitions from the Founding Fathers about avoiding international entanglements, the United States has ratified hundreds of multilateral treaties over the past century. As the accompanying chart shows, more than 630 are in force today.

But recent years have seen a marked slowdown in ratification. A look at the treaty-making process in the United States helps explain why.

Treaty-making involves several basic steps. The U.S. executive branch first negotiates and signs a treaty with international partners. The president then submits the agreement to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC). The SFRC reports the treaty out to the full Senate on a majority vote, after attaching any reservations. Following floor debate, the Senate gives its consent by a two-thirds vote. Finally, the president formally “ratifies” the treaty by signing it.

Delay or treaty failure can occur at any step. The Senate can vote to reject multilateral treaties outright as they did with the United Nations Convention on Persons with Disabilities (CPRD) in 2012.At other times the Senate has approved treaties only after long delays. The most glaring example was the Genocide Convention which took four decades to ratify. In other cases, treaties have never moved out of committee. Finally, in some instances (like the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court), the president has never submitted the signed treaty at all.

Beyond typical executive-legislative struggles, three other factors have complicated timely advice and consent by the Senate.

First, seeking the Senate’s advice and consent to multiple treaties carries heavy opportunity costs. It requires the administration to expend enormous political capital it may prefer to devote to more urgent, competing executive or legislative priorities. It can also require Senate leaders to carve out a week of “floor” time for debate before bringing the treaty to a vote.

Second, treaty type matters: human rights and environmental treaties have an especially hard time. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (1980), the CPRD, and the Genocide Convention are cases in point. These treaties have faced objections of violating U.S. national sovereignty, conflicting with previously existing or state legislation, and touching on sensitive issues like abortion or home schooling. Environmental treaties also generate resistance, based on the perception that they will restrict U.S. business and hamper U.S. economic interests. The Kyoto Protocol is the best-known example but it is hardly alone. Five of the ten multilateral treaties signed by Obama address environmental issues, as do five of the twelve unratified treaties on his 2009 priority list.

Finally, ideology matters: ratification is much more complicated when partisanship is high, especially when the Senate is controlled by Republicans and the White House by Democrats. The outcome of the November 4 elections thus provides ample grounds for pessimism.

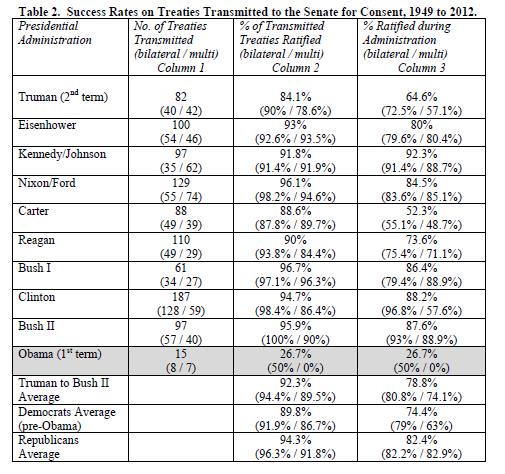

During his first term, Obama averaged only eight treaty transmittals to the Senate for each congressional session, compared to the average of 31.6 treaties per session for the years 1949-2008 (see table below). More importantly, his batting average in getting those approved is well below that of other modern presidents in terms of treaty ratification.

Things have been even grimmer over the past two years, when President Obama submitted only five treaties for ratification. The president has claimed that foreign policy is about “hitting singles.” But when it comes to treaties, he’s rarely getting on base.

The fault lies at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. Compared to recent predecessors, the White House has invested little political capital in treaty-making, focusing on big-ticket domestic items, including the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, as well as Obamacare. At the same time, the White House has made its task harder by seeking approval of more long-languishing treaties on controversial topics like the environment, human rights, and disarmament than other presidents—including George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Jimmy Carter—had signed but failed to ratify. The administration’s priority list submitted in 2009, for instance, included CEDAW, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives, and other Related Materials.

For its part, the Senate seems less open to treaties. It has consented to a smaller fraction of submitted treaties than the average pace. Outright rejection (which has occurred only four times since World War II) remains a rarity. More telling is the Senate’s ability to ignore treaty submissions. But between 2009 and 2012 the Senate approved only one treaty within a year, compared to 510 out of 850 between 1949 and 2000. In other words, the average lag time has increased.

The most important cause of multilateral treaty failure, however, has been the hyperpartisan ideological divide that plagued the 111th, 112th,and 113th Congresses. Particularly noteworthy has been the hard-right shift of the Republican Party. As former State Department legal advisor and adjunct CFR senior fellow John Bellinger wrote in the New York Times, “an increasing number of Republicans had come to view treaties in general (and especially multilateral ones) as liberal conspiracies to hand over American sovereignty to international authorities.”

This gridlock has had two major consequences for U.S. interests.

First, failure to ratify a multilateral treaty that the United States has signed has concrete costs for U.S. foreign and national security policy. Consider the UNCLOS, which remains unratified twenty years after U.S. signature despite being endorsed by every living former president, secretary of state and defense, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, major industry, and leadingenvironmental organizations. Resistance has been led by a vocal minority of conservatives who claim, spuriously, that UNCLOS will undermine U.S. “sovereignty” by subjecting the United States to a supranational legal authority and a massive international tax scheme. In reality, remaining outside the treaty deprives the United States of an effective instrument for extending its sovereignty, by participating in the world’s last remaining partition of territory: namely, the allocation to states parties of hundreds of thousands of square miles in extended exclusive economic zones (EEEZs).

Second, failure to become party to a multilateral treaty endorsed by the vast majority of other UN member states carries reputational costs. The United States relies on its image as a nation dedicated to the international rule of law and a country capable of making credible commitments. Failure to ratify treaties is particularly problematic when, as in the case of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, U.S. negotiators have actually spearheaded multilateral treaty negotiations and shaped the substantive content of international rules to its interests, only to defect at the ratification stage. Such a pattern sends an unmistakable message that the United States is entitled to unique exemptions—that it seeks to constrain and impose obligations on others but refuses to be bound by those same constraints.

Here’s hoping that McConnell and Senator Bob Corker (R-TN)—the likely incoming chair of the SFRC—take these costs into account when they consider the long and growing list of unratified international treaties.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store